Over the years, F1 Front Wings have undergone numerous changes and regulations to improve safety, reduce costs, and increase competitiveness.

What to know

- Front wings first appeared during the 1968 season.

- They are fundamental in managing airflow over and around an F1 car.

- Wings are made up of multiple components, such as endplates, the main plane, flaps, and strakes.

- Without a front wing, cars lose downforce and can potentially take off.

- The 2026 season introduced active aerodynamics for front and rear wings.

In this guide, we will explore the rules and regulation changes implemented by the sports governing bodies, as well as real-world examples, statistics, and interesting facts about the regulations surrounding F1 front winds.

Why do Formula One cars have wings?

A front wing is more than a flashy component on a Formula 1 car. It’s a fundamental part of the car that manages airflow over and around it. Why is this important? Take a track like Monza, one of the fastest tracks on the racing calendar, reaching some of F1’s top speeds. The track demands two things: maximum downforce for stability and minimum drag for speed.

The front wing, with all of its flaps and profiles, helps to meet these demands. It guides air over the top and around the car’s side pods, working with the car floor to create downforce to keep the tyres firmly on the circuit while reducing air resistance (drag) that could slow the car down. Essentially, the front wing is the first point of aerodynamic contact, setting up the airflow behaviour for the rest of the car. A well-designed front wing can improve the car’s overall aerodynamic efficiency, impacting speed, handling, and fuel consumption.

But here’s the catch—designing the perfect front wing is a long and drawn-out process. Technical departments need to balance maximising downforce and minimising drag while adhering to the strict rule book on what is allowed and what is now. Teams that nail it can gain a fraction of a second over one lap, which can build to tens of seconds over a race distance compared to their competitors. It can mean the difference between standing on the podium’s top step or not at the race end.

What if F1 cars didn’t have front wings?

F1 cars achieve speeds on straights high enough for lift-off, like an aircraft. However, the downforce, primarily generated by the car’s aerodynamics, keeps them firmly on the ground. The front and rear wings are crucial in creating this downforce, with the front wing playing a pivotal role. The front wing’s importance cannot be overstated, and without one, a car will begin to lift at speeds. When they fail, things can go spectacularly wrong.

During the 2015 season at the Hungarian Grand Prix, the front wing of the Force India of Nico Hülkenberg failed, firing him into the barriers. When the front wing detached, it slid under the car, first launching Nico Hülkenberg into the air and because he couldn’t break, he was a passenger in an uncontrollable car, eventually crashing into the tyre barriers. Fortunately, Hulkenberg emerged from the accident without any injuries.

As the first part of the car slicing through the air, the front wing has responsibilities extending beyond downforce. It also manages the airflow around the car’s large front tyres, which, if not properly controlled, can significantly disrupt the car’s aerodynamic efficiency. Designers and technicians use simulations on powerful computers to refine the efficiency of these wings; this allows them to play with ideas without creating a physical example. But even if teams get this right, even the slightest damage to the front wing can lead to a substantial performance drop, potentially costing several seconds per lap. More severe damage could jeopardise the car’s and driver’s safety, leading to possible crashes. This is why the front wing is designed for a quick replacement during a pit stop, second only to tyres for how quickly it can be changed.

Design and function

The front wing of an F1 car is an intricate and sophisticated design made up of multiple components such as endplates, the main plane, flaps, and strakes. As we’ve already covered, this part of an F1 car is engineered to create downforce. Downforce is key to pushing the car downwards onto the track, which boosts cornering and straight-line speeds. The design of the front wing is to generate a low-pressure area beneath the wing and a high-pressure zone above it. These pressure differences are key to producing downforce.

Beyond creating downforce, the endplates, positioned at the ends of the wing, are designed to steer the airflow around the car’s front wheels and over and around the side pods. This reduces aerodynamic drag and increases the car’s overall aerodynamic efficiency. The flaps and strakes across the wing are equally important. They channel airflow towards the car’s underbody and, ultimately, the rear diffuser. This directed airflow increases downforce and the car’s aerodynamic performance as a whole.

Technology in front-wing design

While teams are allowed time in physical wind tunnels, they also use the power of advanced Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) software, which lets them model and simulate how air would flow over and around the car. Think of it as a virtual wind tunnel, where teams can tweak and adjust their designs without the costs of creating a physical wing or traditional testing methods.

The CFD software also helps car designers stick to the ever-evolving rule book. This software can become a trusty guide to navigating the FIA’s regulations and flag any potential issues with a wing design. But as with any rulebook there will always be a loop hole somewhere and teams will read between the lines, seeing how the regulations can be interpreted. Finding the smallest gains can mean gaining tenths of a second a lap over a competitor.

When did F1 cars get front wings?

Front wings first appeared during the 1968 season, though the concept had already been explored in other racing categories. The idea of bringing them to F1 can be traced back to Texas, where Jim Hall, an ex-Grand Prix driver, applied an innovative approach. Hall, drawing inspiration from aircraft, theorised that an inverted wing could create a downward force, increasing tyre grip through negative lift.

Hall’s brainchild was the Chaparral 2F, a remarkable sports car from the mid-60s equipped with an enormous rear wing. Unique for its time, the wing was adjustable and attached directly to the wheel hubs instead of the car’s body. Similar to today’s F1 Drag Reduction System (DRS), the Chaparral’s wing angle could be altered by the driver to reduce drag on straights and increase downforce for corners.

Observing this, Colin Chapman the founder of Team Lotus introduced simpler wings on his Lotus 49 at the 1968 Monaco Grand Prix. Chapman’s design included small front winglets and a curved rear metal sheet on Graham Hill‘s Lotus. Hill’s pole position and subsequent victory at Monaco clearly demonstrated the wings’ effectiveness.

The next Grand Prix at Spa-Francorchamps saw Ferrari’s Mauro Forghieri innovating with a genuine inverted wing on Chris Amon‘s Ferrari 312/67, mounted on posts linked to the wheel hubs. Amon’s pole position further emphasised the wing’s advantage.

By the Zandvoort race, almost every car had adopted wings in various designs. However, Chapman didn’t stop there. He developed a full-width rear wing mounted on long supports for undisturbed airflow that required new suspension wishbones and drive shafts.

The large number of wings led to excessively high and fragile designs, resulting in serious accidents when these wings failed. This prompted the FIA to intervene, imposing regulations to ensure safer and less efficient wings, leading to the sophisticated designs seen on today’s F1 cars.

F1 Front Wing regulations

Tracing the evolution of F1 history back to its earlier years, the late 1960s marked the era of rudimentary front-wing designs in the sport. During this period, front wings were basic structures, focusing on function rather than the complex aerodynamics seen in today’s modern F1 cars. They served the straightforward purpose of generating downforce but lacked the sophisticated elements of today’s versions.

The landscape of F1 began to shift as the sport progressed into the 1980s and 1990s. This era witnessed a greater understanding of aerodynamics. Teams started to explore and experiment with front wing designs, gradually evolving towards more complex and elaborate designs with features like adjustable flaps and more intricate endplates.

During the 2000s, F1 and the FIA recognised the need for tighter control and safety measures aimed at reducing speed to enhance F1 safety and help with overtaking. These regulations included mandatory crash tests for front wings, restrictions on the wings’ dimensions, and limitations on movable aerodynamic parts.

From the simplistic designs of the 1970s to the highly regulated and safety-focused approach of the 2000s, it’s clear that the front wing of an F1 car will continue to evolve as the sport does. New aerodynamic rules, materials used, and tighter regulations will always make them an ever-changing part of an F1 car.

2019 F1 Front Wing Regulations

If we rewind to the 2019 F1 season, the FIA took a decisive step towards making the front wings simpler and broader. The underlying reason? To curb the phenomenon of outwash – the manipulation of airflow around tyres that makes it difficult for cars to follow each other closely and overtake. By reducing outwash, the idea was to create a more competitive environment on the track and to increase overtaking for the fans.

However, the sweeping changes did not come without controversy. While some praised the rule changes, they were met with equal scepticism by people in the paddock who questioned their effectiveness in helping overtake. Yet, like all major rule changes, these regulations needed time to prove themselves.

The impact of 2019 F1 Front Wing Regulations on races

The primary objective of the regulation changes for the 2019 season was to boost overtaking opportunities. Ultimately, the change was a huge success statistically, as the 2019 season saw a 20% increase in the number of overtakes. However, as is often the case in F1, the narrative was not as straightforward as the numbers suggested, with voices in the sport highlighting that these changes had a minor influence on the overall thrill factor of the races.

Real-world examples: F1 Front Wings at work

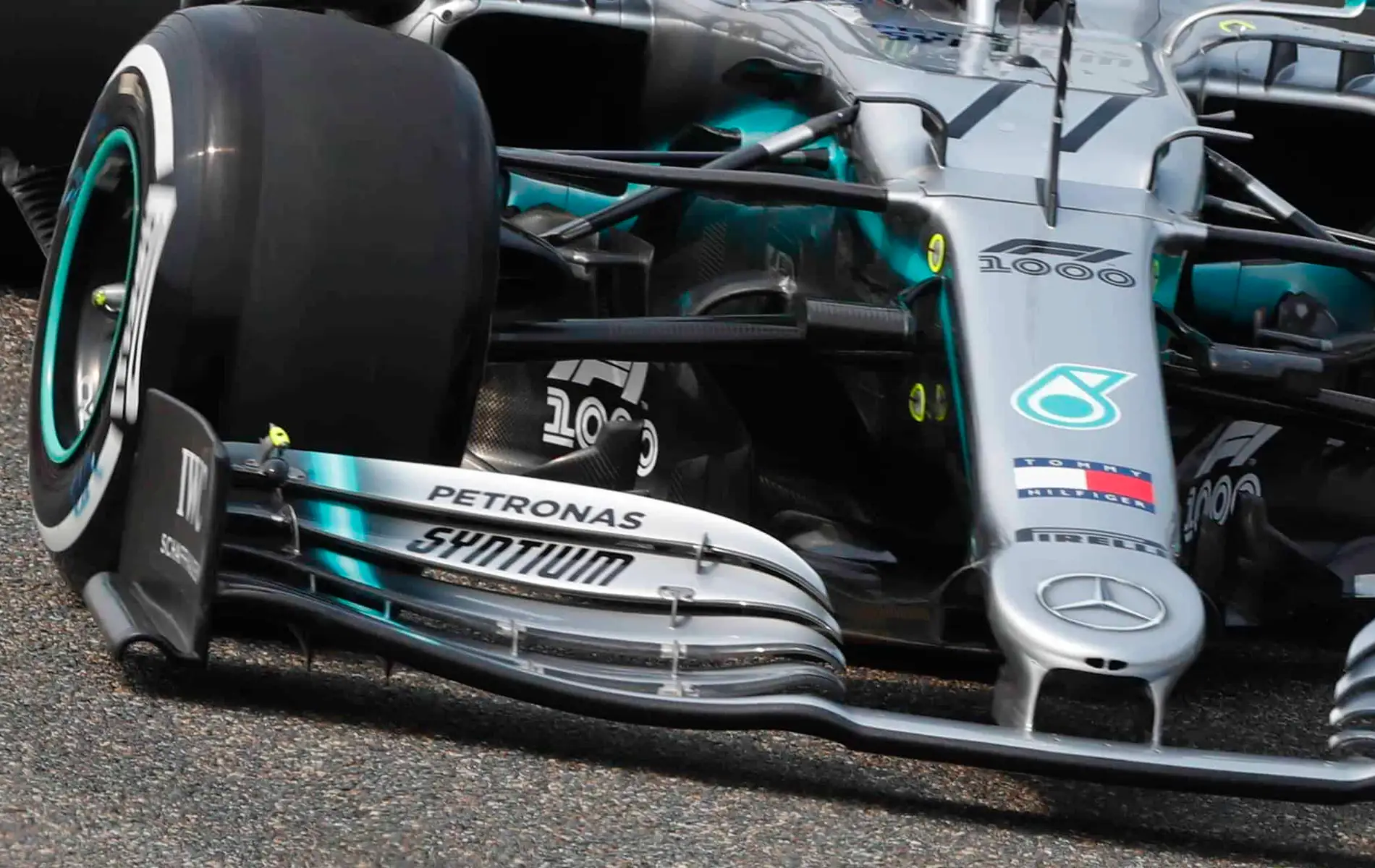

With the 2019 season changes, a great example that year is with the Mercedes team, who caught the F1 paddock’s attention by designing an ingenious ‘cape’ design beneath the front wing for their W10 car.

In the updated 2019 design, the wing featured endplates that were angled outward. This included a notable cutout at the top, designed to help air flow from the wing over the endplate and around the front wheels more efficiently.

This innovative approach was a strategic win in capitalising on the new regulations and maintaining downforce. The result? The team won the 2019 Constructors’ Championship and Lewis Hamilton the 2019 Drivers’ Championship. On the other hand, Ferrari, who were their closest rivals that season, opted for a more conventional wing design, which couldn’t quite match the performance and failed to beat them to either championship.

These different approaches highlight how teams can adapt to regulatory changes quickly. While Mercedes and Ferrari are just two examples, they demonstrate the game of balancing innovation with regulation in the quest for that crucial edge in performance.

How much does a F1 wing cost?

The combined cost for an F1 front wing and rear wing in a Formula 1 car reaches an impressive $250,000 (€236,887). This considerable cost can be credited to the design time and the manufacturing to suit each team’s individual needs and specs.

This time involves extensive R&D, with teams investing heavily in aerodynamics to optimise the car’s performance. Each wing is not just a standalone component, either. Its design must work harmoniously with the vehicle’s chassis, suspension, and other aerodynamic elements, such as the floor and plank. The design process involves advanced CFD, wind tunnel testing, and constant refinements throughout the season to achieve the perfect balance of downforce, drag, and stability.

The cost of materials used in constructing these wings also drives up costs. These materials will involve cutting-edge composites and alloys to ensure strength, durability, and lightweight.

F1’s 2026 ‘active aerodynamics’

Starting for the 2026 F1 World Championship, Formula 1 cars will ditch the current Drag Reduction System (DRS) in favor of active aerodynamics—movable front and rear wings designed to boost overtaking and on-track excitement.

Drivers will have two aerodynamic modes at their disposal:

- Z-Mode (Cornering Mastery): Adjusts wing angles for higher downforce and improved grip through corners.

- X-Mode (Top Speed): Flattens the wings to reduce drag, maximizing speed on straights.

While drivers will control when to switch modes, usage will be restricted to FIA-approved safe zones, typically long straights lasting over three seconds.

This shift places a greater emphasis on driver skill and strategy, ushering in a new era in which overtaking becomes a more tactical, calculated art.

The future of F1 Front Wing design

While some Formula 1 enthusiasts advocate for a shift towards even simpler front wings, an idea aimed at increasing the level of competition and allowing more overtaking, others predict a future that leads to designs that are even more complex. F1 is a sport that pushes for the latest state-of-the-art materials and precision engineering, so teams will always push for more and more performance each season. Of course, regulatory bodies like the FIA and Formula 1 will always be involved, constantly scrutinising the line between technical innovation and sporting fairness.

Seen in: