In the early years of the championship, which began in 1950, cars predominantly ran in national racing colours, such as red for Italian cars like Ferrari and green for British cars. The shift towards commercial sponsorship didn’t begin till the late 1960s when a privateer and full works team pioneered the way.

It wasn’t until 1968 that the FIA relaxed their rules on team sponsorship after firms like BP, Shell and Firestone withdrew support from the series. Seeing the potential that the investment could bring, several teams took no time in securing deals.

Who was the first F1 sponsor livery?

The South African privateer team, Team Gunston, took advantage of the FIA changing their rules and became the first Formula One team to paint their cars in the livery of their sponsors.

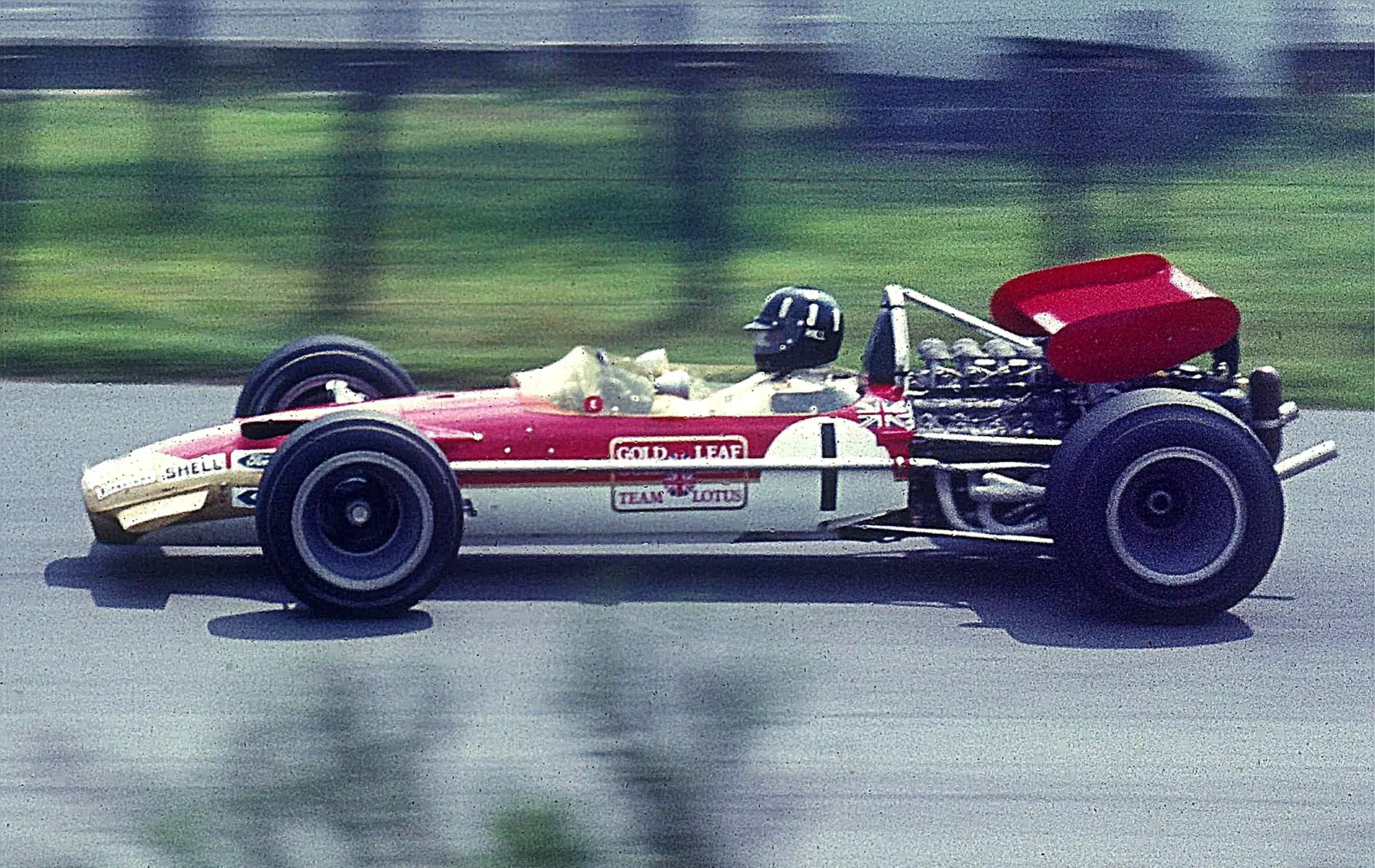

Painted in the colours of Gunston cigarettes, the team entered a private Brabham with John Love at the 1968 South African Grand Prix. In the next round at the 1968 Spanish Grand Prix, Team Lotus became the first works team to secure a significant sponsorship when they partnered with the tobacco company Imperial Tobacco.

The team displayed the livery of their Gold Leaf tobacco, with Graham Hill‘s Lotus 49B adorned in the brand’s Red, Gold, and White colours. This landmark deal started commercial sponsorship in F1 and led to the many colourful and often branded liveries we see today.

History of Sponsorship in Formula 1

The 1960s were a transformative period in the sport, with Team Lotus pioneering not only sponsorship deals but also technology.

While competing on track, teams were also in an arms race in the design studios and testing facilities to build the fastest and most advanced cars on the grid. F1 Teams invested heavily in R&D, experimenting with new designs, materials, and technologies to gain even the slightest advantage over their rivals.

The decade also saw a greater understanding of aerodynamics. Cars began to feature sleek, streamlined bodywork and innovations like front and rear wings started to appear, altering not only the look of the cars but also increasing their performance, speed and handling.

Lightweight and strong materials like aluminium, titanium, and various alloys started to replace traditional steel frames in many cars, which improved not only speed but also F1 driver safety. The ’60s also saw significant developments in engine technology. There was a move towards more powerful and efficient engines, with teams experimenting with different configurations and fuel mixtures to extract the maximum performance from them.

While these boundaries were being pushed, they also created a significant strain on team finances. R&D, testing, and engineering required substantial investment in skilled personel, state-of-the-art facilities, and cutting-edge equipment.

As the costs began to rise, a clear financial disparity began to emerge between teams. Those with deeper pockets could invest more, often leading to better performance on the track. Given the escalating costs, self-funding or relying solely on prize money became untenable for many F1 Teams. To stay competitive, teams had to look beyond traditional sources of income. The FIA relaxing its rules paved the way for external sponsorships, such as the groundbreaking deal between Lotus and Gold Leaf, which set the sport off in a new commercial direction.

Colin Chapman’s vision

Colin Chapman, the founder of Team Lotus, was not just an engineer; he was also a visionary when it came to understanding the commercial potential of motorsport. His pursuit of performance had led Lotus to become one of the most successful teams in the sport’s history, but he also understood the mounting financial pressures that came with it.

Chapman was acutely aware of the ballooning costs and the increasing difficulty in funding a team purely from prize money or traditional sources of investment.

While most teams in the 60s still took the old-school approach of painting their cars in national colours and relying on automotive sponsors like BP or Firestone. Chapman was more forward-thinking. He saw potential in looking for sponsors outside of the sport to broaden the commercial appeal of his team.

Chapman’s decision to embrace Tobacco sponsorship was not just about getting funds. It was about creating a relationship where brands could leverage the popularity and global appeal of F1, and in return, teams could benefit from the significant financial input. This approach would ensure a steady flow of income to support the team’s ambitions on and off the track.

Chapman’s vision set a precedent. By aligning with Gold Leaf, he demonstrated to the rest of the paddock that there were vast, untapped reservoirs of money outside the motoring sector. The move was a game-changer for the sport, leading to a rush of new sponsorships. Colin Chapman’s ability to think outside the box reshaped how teams approached financing forever.

Tobacco money in Formula One

The relationship between tobacco companies and sports sponsorship during the latter half of the 20th century was profound. During the 1960s, tobacco companies were among the most profitable brands in the world. With vast marketing budgets at their disposal, these companies were continuously seeking platforms to showcase and advertise their products.

While print media, television, and billboards were primary advertising channels for tobacco brands, sports offered something unique. A car speeding past with a tobacco brand logo was not just an advertisement; it was a statement of speed, power, and prestige.

Formula 1 was and still is a glamorous sport with a global reach and an association with cutting-edge technology. It was particularly attractive to tobacco brands as it aligned with their brand vision of luxury, excitement, and a hint of danger.

Seeing an opening in this high-profile sport and recognising the Lotus and Colin Chapman as strong partners, Imperial Tobacco took the leap into F1. Their decision to sponsor Lotus and introduce the Gold Leaf livery was groundbreaking as it embedded the Gold Leaf identity into the very fabric of the Lotus team.

The success of the Lotus-Gold Leaf partnership did not go unnoticed. Soon after, other tobacco brands recognised the potential of F1 as a valuable advertising platform. Marlboro’s association with McLaren, Rothmans with Williams, and Camel with Benetton are just a few examples of other significant tobacco sponsorships that followed.

While the influx of tobacco money brought significant financial benefits to the sport, it wasn’t without its controversies. The health effects of smoking became more recognised, and public sentiment shifted; there were growing concerns about the ethics of tobacco advertising in sports. This would eventually lead to stricter regulations and the phasing out of tobacco sponsorships in many sports, including F1.

Impact on F1

The association of racing cars with national colours was a long-standing tradition in motorsport. These colours, often called “racing colours,” held symbolic significance, representing the countries the teams came from. For instance, British cars were typically painted in British racing green, Italian cars in rosso corsa (racing red), and French cars in blue. Tying the performance and engineering of the cars to national pride and identity.

When Lotus, under Colin Chapman’s vision, partnered with Imperial Tobacco’s Gold Leaf brand, it wasn’t just about adding a logo to the car. The iconic red, white, and gold livery of Gold Leaf enveloped the entire car, transforming its visual identity. This was a clear departure from the norm, signalling that commercial interests could take precedence over traditional national representation.

The success of this partnership—both in terms of financial and brand visibility—did not go unnoticed by other teams. Realising the potential of commercial sponsorships, many began to court companies outside the automotive realm. As more teams adopted this model, the grid transformed, with vibrant and varied liveries replacing the once-uniform national colours.

The injection of significant sponsorship money had a profound impact on F1. Previously constrained by limited funds, teams now had the financial capability to delve deeper into research and development. State-of-the-art facilities sprouted up, equipped with advanced machinery, wind tunnels, and simulation tools. These investments allowed teams to experiment, innovate, and refine their cars

The increased budgets meant teams could now attract the best talent, not just behind the wheel but also behind the scenes. World-class engineers, aerodynamicists, strategists, and other specialists flocked to F1, lured by competitive salaries and to work in a space pushing ideas.

With more money, driver salaries also saw a significant boost. Top F1 drivers became some of the highest-paid athletes in the world and became increasingly marketable.

As technology advanced on track, tech giants and car companies became increasingly interested in collaborating with teams, exchanging and co-developing ideas that would trickle down to commercial road cars. Innovations like active suspension, semi-automatic gearboxes, and advanced telemetry systems became the norm while cars became faster and safer.

Combined, the visual appeal of advanced, sleek cars further increased F1’s global appeal. Broadcast deals, merchandise sales, and event attendance grew, creating the sport as we know it today.

However, money doesn’t come without its challenges. As costs soared, there were concerns about the sport becoming unsustainable for some teams. This has led to new regulations in the early 2020s with budget caps and fairer prize money distribution to ensure a more competitive balance for the sport’s long-term health.

Regulation changes against tobacco sponsorship

As global awareness of the health risks associated with smoking grew, so did the scrutiny and ethics of tobacco advertising in F1.

Starting in the late 20th century, mounting scientific evidence began linking tobacco use to various health conditions, including lung cancer and heart disease. This led to anti-smoking campaigns gaining momentum and governments starting to take notice.

This led to restrictions on tobacco advertising in several countries during the 1970s and 1980s. These often came as bans on television and radio commercials for tobacco products. However, sports sponsorships, including those in F1, were initially exempt from these restrictions.

By the 1990s, the global anti-smoking movement had gained significant traction. International bodies like the World Health Organisation were vocal in criticising tobacco advertising. The highly visible nature of cars, racing at famous F1 circuits worldwide, made them a focal point of this criticism, especially given the sport’s appeal to younger audiences.

In the late ’90s and early 2000s, the European Union moved to ban all tobacco advertising and sponsorship in sporting events by the mid-2000s. Similar legislation was enacted in various other countries where F1 races were hosted. As these regulations took effect, teams began phasing out their tobacco sponsorships. Some teams adopted creative solutions like Ferrari using barcodes to replace Marlboro advertising and only displaying tobacco branding in countries where it was still legal.

Over time, visual sponsorship was phased out but some teams maintained their relationships with tobacco companies in subtler ways, leading to debates and controversies. Eventually, teams secured partnerships with brands from other sectors, from technology and energy to fashion and finance, which has led to a more varied and colourful grid.

The future of sponsorship in F1

The Lotus-Gold Leaf partnership transformed F1 from a sport primarily funded by automotive manufacturers and wealthy individuals to a global commercial platform attracting sponsors across all industries.

While tobacco sponsorships played a role in shaping Formula 1 for many years, changing moral values and stringent regulations on tobacco brands meant the sport had to adapt again, creating new partnerships and finding other ways to grow the franchise. With betting firms and cryptocurrencies sponsoring teams in the 2020s, maybe over time, these might be phased out as even these are viewed as unethical in some circles. If they are, F1 will no doubt find another way to push the boundaries of sports sponsorship.

Seen in: